This is a longer feature story designed for a magazine format, as yet unpublished . It tells a much more personal story; beginning with “I didn’t meet the love of my life, Sheila, until i was about forty…”

It reveals how a bottle of Irish malt whisky helped to unlock a secret past that Sheila had never heard of, linking her father with key moments in Irish history.

A visit to Ireland to confirm those links later led to another revelation – her father had led a secret life in which he had been a fugitive from justice, and Sheila had been using a false name all her life…

I didn’t meet the love of my life, Sheila, until I was about forty; the picture below shows the magic of her smile.  By the time we married, I was nearer 50. One consequence of this was that her parents were quite elderly when I first went to stay with them. Feeling quite nervous about it, I took a bottle of Irish malt whiskey as a gift. Her father Frank (Paddy) Ryan was not a big drinker, but I wanted to acknowledge his Irish roots in a positive way.

By the time we married, I was nearer 50. One consequence of this was that her parents were quite elderly when I first went to stay with them. Feeling quite nervous about it, I took a bottle of Irish malt whiskey as a gift. Her father Frank (Paddy) Ryan was not a big drinker, but I wanted to acknowledge his Irish roots in a positive way.

He was born in County Cork in the Irish Republic, but like many of his generation he had crossed the water to England and served with distinction in the Royal Warwickshire regiment throughout World War Two, having joined up as a regular soldier in the 1930’s.  He is shown here with his wife Margaret Sparrow and their son David, in Warwick. His platoon went to France with the British Expeditionary Force in 1940 and fought as part of the rear guard at the Battle of Dunkirk, delaying the Germans while the other troops were evacuated. Sadly, an SS unit captured and murdered many of his friends in the notorious ‘Wormhoudt massacre’ after the battle. Because he was a crack shot with the rifle and mortar, he went on to spend the rest of his war training new recruits back in England, ending up as a Staff Sergeant.

He is shown here with his wife Margaret Sparrow and their son David, in Warwick. His platoon went to France with the British Expeditionary Force in 1940 and fought as part of the rear guard at the Battle of Dunkirk, delaying the Germans while the other troops were evacuated. Sadly, an SS unit captured and murdered many of his friends in the notorious ‘Wormhoudt massacre’ after the battle. Because he was a crack shot with the rifle and mortar, he went on to spend the rest of his war training new recruits back in England, ending up as a Staff Sergeant.

Later, we met someone who had been trained by him in the army. He told us that Paddy was famous in his own quiet way, simply because he was the only Sergeant in the British army who had never, ever, been known to swear at the men under his command. Sheila thought this was because he’d been very badly treated by the Christian Brothers as a boy in Ireland, and he’d vowed never to bully others. Not that Paddy suffered his own bullying in silence; he was always a ‘little soldier’. He often hid up a tree and threw stones down at the Brothers as they walked past below, and on one occasion he dragged the Brothers’ donkey up the spiral stairs into the church bell tower. When the bells rang the donkey panicked, brayed loudly for hours, and refused to descend. His relatives feared for his future, thinking he would become a ‘bad lad’, and were much relieved when he joined the army. In fact he was a gentle, self-effacing man in civilian life, adored by Sheila and her siblings, by his wife ‘Molly’, and by his grandchildren.  Here he is holding Catherine, one of his grandchildren After the war he became a skilled tool-setter at Lockheed and was rapidly elected as the shop steward. Despite this role (and his exemplary war service) when the Birmingham pub bombings occurred he was ‘sent to Coventry’ by his work-mates, simply for being Irish.

Here he is holding Catherine, one of his grandchildren After the war he became a skilled tool-setter at Lockheed and was rapidly elected as the shop steward. Despite this role (and his exemplary war service) when the Birmingham pub bombings occurred he was ‘sent to Coventry’ by his work-mates, simply for being Irish.

So I was very pleased to see that he reacted to the bottle of malt whiskey with a broad smile; with a twinkle in his eye he asked if we would like to share some (as I hoped he would). He then asked Sheila to pour the drinks, explaining to her that back in County Cork in his day it was considered bad luck if the men had to pour their own drinks. He began to talk to us about other memories of his upbringing in rural Ireland, things that Sheila had never heard before. It’s amazing what doors a good malt whiskey will open…

Because he had lived through the war of independence and the civil war that followed, I was very curious to know if he had any memories from that time. He paused for a moment, then nodded, “Ah, now, I did meet Michael Collins once, in my uncle’s pub, he must have been recruiting for the Volunteers at the time.”

My mouth fell open; “Really?”

“Oh yes, but I was only a little lad, so they often made me hide under the table out of sight, and I only really met his boots. They called him ‘the big feller’, and he had big boots all right. That’s mainly what I remember, his big boots.” (Paddy’s mother had worked on the White Star liners, and I knew that as a child he had been passed from pillar to post while she was away at work, so this was not as implausible as it may sound to modern ears… but this was not all…)

“Another time, I’d be about nine, I got caught in the middle of a fight between ‘the boys’ and the British army.” (‘The boys’ is the name that the population of rural Cork used for the Irish Volunteers, later known as the Irish Republican Army.)

“What sort of a fight?”

“A proper shooting match, it was. I was just walking across the bridge in Fermoy one Sunday morning and suddenly I got shoved to the floor by a British soldier. And then the shooting started. And the feller who pushed me to the floor, he took a bullet and fell on top of me. He was wounded, so he was, and he bled all over me.”

“Did he live?”

“Ah, he did; but there was one or two that didn’t. The boys were after their guns, you see, and they got way with most of them.”

Sheila was a little sceptical about these stories, having never heard either before. But Paddy did not generally make up stories or tell untruths; far from it, he had a reputation for scrupulous honesty. However, he was 85 at the time and we suspected that he had a brain tumour (later confirmed). As a doctor, she thought he might be mixing his army and childhood memories up.

So when we got home, I went to the history books and looked up Fermoy in the troubles; and there it was, exactly as he described it to us, right at the outbreak of the troubles in September 1919 (he was indeed 9 years old) in his home town. One Sunday morning, in one of the very first raids of the troubles, a group of ‘the boys’ with revolvers and shotguns held up British soldiers as they emerged from Christchurch, which stands right next to one end of the bridge crossing the River Blackwater. The raid was largely successful, but at some point a brief firefight broke out which left several soldiers wounded, and two later died of their wounds. (What Paddy did not mention is that some of the other soldiers later took revenge by smashing up property in the town on a drunken rampage.) Nevertheless, the implication we took from his story is that the British soldier had probably saved his life by pushing him to the floor at the critical moment. This act certainly made him want to be a soldier, and it also explains why he joined the British army despite coming from a staunchly republican area…

A few years later (after his death) we traveled to Ireland to visit the family who had fostered him and talked to his foster brother (now in his 90’s but still sharp as a needle) who confirmed the truth of both stories. “Ah now, that would be right, Fons told me about seeing the big feller back then, and about the shooting on the bridge.” Throughout our conversation, he and the others in his family kept referring to Sheila’s father (Frank ‘Paddy’ Ryan) as ‘Fons’, so my wife asked if this was his nickname. “Oh no,” came the reply, “that was his name back then, Alfonsus Gilligan… he had to change it when he joined the British army the second time…”

Sheila’s brows furrowed at this. “What do you mean, his name back then?”

“That was his real name, Alfonsus Gilligan, here in Ireland. Didn’t you know that?”

So that’s how my very respectable doctor wife discovered that she had had a false name all her life… and set us both off on a trail to discover the details of Fons’ secret life, before he became Sergeant Paddy Ryan… and why this change of name was so necessary…

We discovered a fascinating tale of struggle and resilience in the face of enormous difficulty; yet also a tale that was probably typical of that generation who were children during the struggle for independence. Many were forced to emigrate to find work; independence was followed by a disastrous civil war, a trade war with Britain, and then a world-wide depression.

My own mother, shown here in 1946,  met another County Cork man, a handsome merchant navy engineer on the Atlantic convoys, while serving beer in her father’s pub. Those convoys were Britain’s lifeline during world war two; the merchant navy literally kept Britain alive. Pat had sung at the New York Metropolitan opera house (and had the publicity photos to prove it). He was also twice sunk by U-boats, and survived each time. Perhaps he had secrets, too.

met another County Cork man, a handsome merchant navy engineer on the Atlantic convoys, while serving beer in her father’s pub. Those convoys were Britain’s lifeline during world war two; the merchant navy literally kept Britain alive. Pat had sung at the New York Metropolitan opera house (and had the publicity photos to prove it). He was also twice sunk by U-boats, and survived each time. Perhaps he had secrets, too.  With his talent, why hadn’t he settled in America? Why traverse the globe, fixing engines on tramp steamers?

With his talent, why hadn’t he settled in America? Why traverse the globe, fixing engines on tramp steamers?

All her life, my mother kept her face powder in a small wooden bowl with a mirror in the lid. After her death we discovered that carved inside this bowl, under the powder, was the inscription, “To the sweetest and dearest person I’ve ever known, love, Pat”. She had never forgotten him.

Meanwhile my father spent his war years in north-west India (now Pakistan, near the Afghan border) where he found himself bridging two worlds – that of the old-fashioned Raj and the new India-to-be. Called up as a newly qualified maths teacher, the army put him in the Royal Signals and sent him overseas to train soldiers in signalling techniques. In Peshawar, he developed a close friendship with an Indian signals officer (Captain Ananda Mehra, known as ‘Andy’) with whom he worked – see the picture of the them together,  in fancy dress. When he returned from a visit to the Mehra family home, he also found himself ‘sent to Coventry’ by the other British officers and soldiers. I’m proud to say this did not deter their friendship or inhibit my father’s love of curries from the bazaar. The army solved the problem by letting him work mostly with Indian and Gurkha regiments. He amassed a wonderful archive of black and white photographs; the examples shown here are a small sample from his collection.

in fancy dress. When he returned from a visit to the Mehra family home, he also found himself ‘sent to Coventry’ by the other British officers and soldiers. I’m proud to say this did not deter their friendship or inhibit my father’s love of curries from the bazaar. The army solved the problem by letting him work mostly with Indian and Gurkha regiments. He amassed a wonderful archive of black and white photographs; the examples shown here are a small sample from his collection.

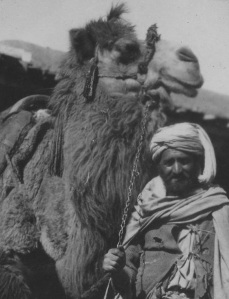

The camel trader shown below was taken in 1944 when he acquired some Persian and Afghan carpets from merchants coming over the Khyber pass. He packed the carpets up in a trunk and sent them home, part of a consignment due to travel on a certain ship. Unfortunately, he soon heard that this particular ship had been sunk by a Japanese submarine! He didn’t buy any more carpets after that. But much to his surprise, after he’d been home 18 months the trunk and the carpets turned up, undamaged… better late, than never!

was taken in 1944 when he acquired some Persian and Afghan carpets from merchants coming over the Khyber pass. He packed the carpets up in a trunk and sent them home, part of a consignment due to travel on a certain ship. Unfortunately, he soon heard that this particular ship had been sunk by a Japanese submarine! He didn’t buy any more carpets after that. But much to his surprise, after he’d been home 18 months the trunk and the carpets turned up, undamaged… better late, than never!

Like many overseas soldiers, he received a dreaded ‘Dear John’ letter breaking off an engagement to a girl back home. But he rapidly learned to enjoy being a bachelor in India, as his photo archive proves…there a number of photos of him with various pretty girls, such as this one with a very

attractive Anglo-Indian girl and her sister, by a waterfall in Kashmir. While there, he took the picture below titled ‘urchins in Kashmir’. Some of his photos also show a darker side to his experiences; the bodies of tribesmen killed by their own (tribal justice) or by the British when they attempted to raid the army bases for weapons. There were regular ‘tea parties’ with the Pathan chiefs in order to smooth out these incidents. After the war, he became a respected headmaster at a northeast comprehensive school; few people knew about his secret life in India during the war.

attractive Anglo-Indian girl and her sister, by a waterfall in Kashmir. While there, he took the picture below titled ‘urchins in Kashmir’. Some of his photos also show a darker side to his experiences; the bodies of tribesmen killed by their own (tribal justice) or by the British when they attempted to raid the army bases for weapons. There were regular ‘tea parties’ with the Pathan chiefs in order to smooth out these incidents. After the war, he became a respected headmaster at a northeast comprehensive school; few people knew about his secret life in India during the war.

On the home front, my mother’s father was a different kind of hero – a man who not only stayed loyal to a wife whose mental health went gradually but very, very steeply downhill, but somehow managed to raise their six daughters almost single-handed. The picture shows them on their wedding day. He ran several small businesses (including the pub) throughout the thirties and forties in a remote corner of the northern dales. Those daughters grew up to become loving and generous aunts to my generation, but the stigma of mental illness left a veil of secrecy over their childhood; added to by darker secrets when one of the sisters died in mysterious circumstances, just after the war.

That generation led such fascinating lives that I decided to merge their stories into a novel. It begins in Ireland, with that shoot out on the bridge. What connects a normally sleepy Irish town with a remote corner of the northern dales? How do these dales become a refuge from a terrible past and the horror of war? The story can be summarised as an Irish ‘Midnight’s Children’ meets ‘Ryan’s Daughter’, travels the globe, and becomes a northern dales version of ‘When the boat comes in’…

So, read my book to discover an Anglo-Irish saga and romance… and, since 10% of the English population have an Irish grandparent, and another 25% have connections going back much earlier then a lot of people are descended from such romances… the title of the book, ‘Crossing the Water’, is Irish slang for emigration…